Video

A Conversation with Ava DuVernay: Resistance, Storytelling, and Film

Professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad was joined by Oscar-nominated filmmaker and screenwriter Ava DuVernay in JFK Jr. Forum

Q+A

A Conversation with Eternal Polk, Director of Gaining Ground, a new film about reclaiming Black land in the US

Black land ownership in the US today has dwindled to historically low numbers. In 1910, Black farmers owned about 14% of agricultural land in the U.S. Today, a staggering 90% of that land is no longer in Black hands. That amounts to an estimated loss of $326 billion denied to generations of Black Americans — a significant contributor to the U.S. racial wealth gap.

To help reverse this trend, a network of farmers, activists, and historians are leading a fight to reclaim Black land and create paths to economic justice. Among them is Eternal Polk: a two-time Emmy-nominated filmmaker and director of the new documentary Gaining Ground: The Fight for Black Land.

On November 29, Eternal Polk will join the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project (IARA) and the Institute of Politics (IOP) at the JFK Jr. Forum for a screening and panel discussion about the film.

On November 29, Eternal Polk will join the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project (IARA) and the Institute of Politics (IOP) at the JFK Jr. Forum for a screening and panel discussion about the film.

Ahead of the event, the IARA team caught up with Eternal for a Q&A exploring his role as a creative and filmmaker in the fight for racial justice:

Your new documentary ‘Gaining Ground: The Fight for Black Land’ explores the little-known history of Black land loss — which is a prime example of a history at risk of erasure. As a creative and filmmaker, how do you see your role in telling this history?

Eternal Polk: I see my role like the griots [traditional storytellers from West Africa] — sharing our history so it is not forgotten or erased. I’m a steward of the story and sharing it so others can know and share. History is easily erased when it exists on an individual basis and with a limited audience. It’s important to share this story as a documentary in particular because it becomes almost a statement of record. This is good and bad, depending on the intention and objective of the filmmaker. My intention was not only to bring the issue to light, but guide the audience on how this all started, and what is happening now, and the resources available for them. Film holds a special place for folks because when they see it and are moved by the people and places they see, it resonates and sticks with them.

Capturing nuance in film can be challenging, especially when covering complex issues like the theft of land. The documentary features candid interviews with diverse voices involved in Black land ownership today, ranging from historians to activists, landowners, and farmers. How do you make sure to capture and convey the nuance in representing them?

Capturing the nuance of an issue or person starts with knowing the person or situation, which happens in research and pre-interviews. But you also have to be willing to dig a bit for the nuance and be honest about what you find. Nuance requires you to be authentic with the subject matter and honest with yourself about what you want to reveal. In this process I connect with the subject and people, and with that, I want to represent them fully and honestly at the end of the day.

I have a huge fear of disappointing people who trust me to share their story and reveal themselves to me, so I do my best to show them in their complexity and with that nuance so what the audience sees is a complete person and not an archetype or stereotype or caricature of who they are. As far as the subject or issue, it deserves the same respect and the audience deserves to be given an accurate and genuine conversation because they’re committing their time, thoughts, and feelings for 90+ minutes… I take all of that very seriously — the commitment everyone involved is making. This is why nuance is important… God is in the details and I want everyone walking away with a complete understanding of everyone involved, and even themselves in relation to what they’ve just seen.

The history of Black land ownership in the U.S. is interwoven with multiple justice issues, from food justice to Indigenous land rights and intergenerational wealth creation. In making this film, did anything surprise you about these intersections?

From my perspective in the U.S., Black people are the intersection. Whether it’s us toiling on, nurturing and dying for and on the land in this country, or us fighting for rights of all marginalized and oppressed peoples in the land, while that fight benefits everyone including folks who at times were against it. Nothing really surprised me because I’m well aware of how we as Black folks are interwoven into the fabric of this country. That includes enslaved and formerly enslaved folks and our relationship with Indigenous people. The one thing that did standout to me was the thought process of Black folks coming out of slavery and owning land. The vast majority of folks were thinking generationally; they were thinking of this land as their ancestral land… I think within the last few decades of land ownership, the idea was to use land to flip and get a bag, but now I think that ideology is changing more to an idea of generational ownership and a place for your people to truly call home and live with a certain degree of peace and autonomy.

The film tells the history of Black land ownership through the lens of resistance, centering the fight for Black land and economic justice. How much of ‘resistance’ is in your art versus your life outside of your work?

Good question. I have always advocated for justice and supported my friends who have been in these spaces of activism and directly fighting for justice for marginalized and oppressed people and those embroiled in the injustice system. I always feel like I could do more, honestly. This film is my offering and my contribution, and my participation in it inspires me to be more active and frankly do more.

I do believe it is important to have balance as an artist if you’re in a space where your work inevitably lives in the social justice or community framework. It’s all individual of course, but I want to create purely entertaining works that are an escape as well as work that compels the audience to “do” something. Even in this, if your ideology, I mean personal ideology, is for liberation or eradicating injustice, it leaks into work that is meant purely for “entertainment”.

Lastly, who are you hoping to reach with the film? What do you want them to take away?

I’m hoping to reach the communities — all communities — affected by this, and hopefully they have a solid foundation in understanding what is happening and 1) how they can prevent this from happening to them, 2) what to do and what resources are available if they are currently dealing with this, 3) How they can help or be an ally in this fight. Lastly, in particular, I want Black and brown folks who have this disdain or fear for rural spaces, woods and the outdoors to start to develop a love for the land and what it can bring and provide in all aspects of their lives including healing. Our blood is in the soil and the foundation of America’s success and greatness. We deserve to enjoy this land, the lakes, the mountains, the woods, the hills and quiet paths as much as anyone in America… I want us to be inspired to get land, shed that fear of rural areas and outdoors that some of us hold and embrace what we’ve contributed to in this country… I want us to enjoy the beauty of what America is as a land… we have a lot of work to do in this society to make it fair and equitable, and to me it starts with the land, because all things come from it … and all things will return to it.

This Q+A was written prior to a screening of and discussion about the film that was hosted in December 2023. To watch the discussion about the film, click here.

Art, entertainment, and sports shape American life. As cultural pillars, they reflect who we are, what we discuss, and which stories we remember. For better or worse, they form how we see each other — and how we see ourselves.

This year, the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project (IARA) is partnering with the Institute of Politics (IOP) to host a series of three talks by nationally recognized speakers addressing the theme ‘Culture of Change: racial equity in art, entertainment, and sports’.

This IOP Speaker Series will explore themes including art as a form of protest, the value of entertainment in shaping political discourse, and the historical reckoning of cultural institutions with their legacies of injustice.

Video

Professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad was joined by Oscar-nominated filmmaker and screenwriter Ava DuVernay in JFK Jr. Forum

Video

Artist Hank Willis Thomas spoke with Harvard professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis about how love guides his artwork at a Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics forum.

Feature

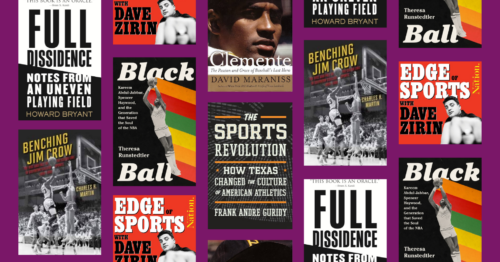

This reading list from the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project explores the intersection of sports and racial justice, in the lead-up to their panel on March 19.

Video

Professor Khalil Gibran Muhammad was joined by Oscar-nominated filmmaker and screenwriter Ava DuVernay in JFK Jr. Forum

Video

Artist Hank Willis Thomas spoke with Harvard professor Sarah Elizabeth Lewis about how love guides his artwork at a Harvard Kennedy School Institute of Politics forum.

Feature

This reading list from the Institutional Antiracism and Accountability Project explores the intersection of sports and racial justice, in the lead-up to their panel on March 19.